The Problem: Why Traditional Fact-Checking Fails

Most existing automated fact-checking systems have a fatal flaw: they rely on static knowledge bases (like old Wikipedia dumps). If a rumor starts today about a breaking event, those systems are useless. Furthermore, relying on a single AI model often leads to high variance—sometimes the model hallucinates, and sometimes it’s just confidently wrong.

I wanted to solve four specific challenges:

-

Complexity: Claims often contain multiple sub-truths.

-

Dynamism: Evidence needs to come from the live web, not a static database.

-

Transparency: The system needs to explain why it made a decision.

-

Multimodality: It needs to handle text and images.

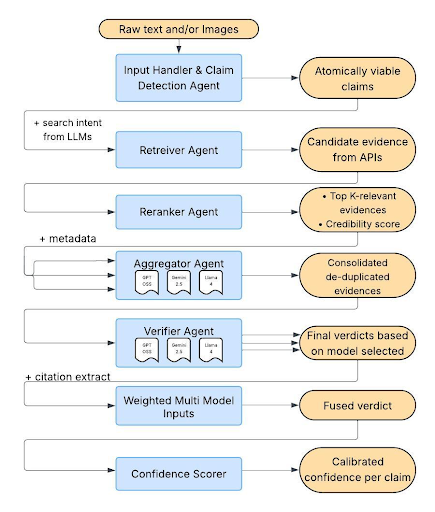

The Architecture: Under the Hood of KEPLER

I designed KEPLER as a modular, seven-stage pipeline. Let me walk you through exactly how a claim travels from a user’s input to a final verdict.

1. Input Processing and Claim Decomposition

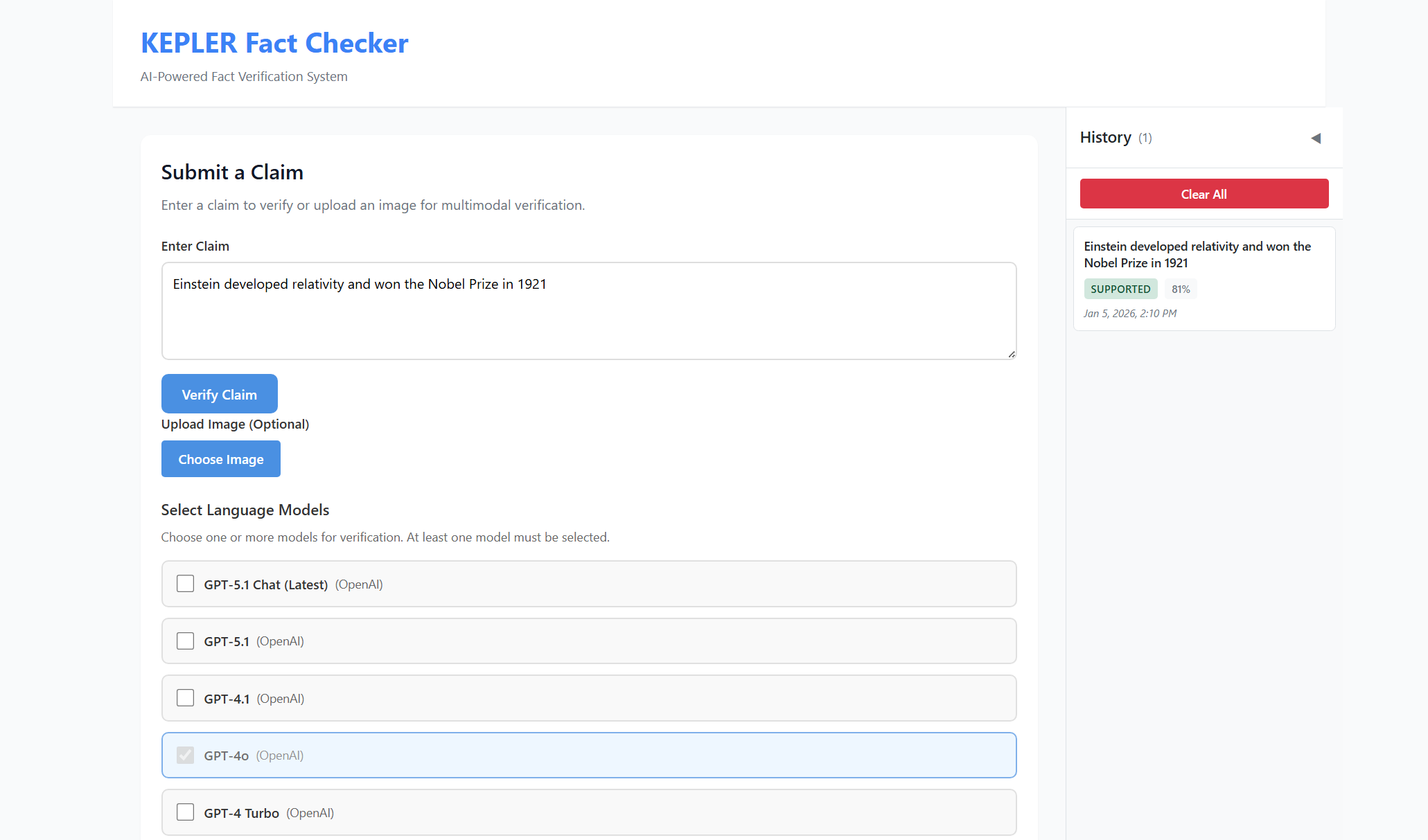

KEPLER accepts multimodal inputs consisting of a textual claim and/or an accompanying image.

Users select from a pool of available LLMs (GPT 4o, GPT-4o-mini, GPT-3.5-turbo, Claude 3 Haiku, Claude Sonnet) for verification.

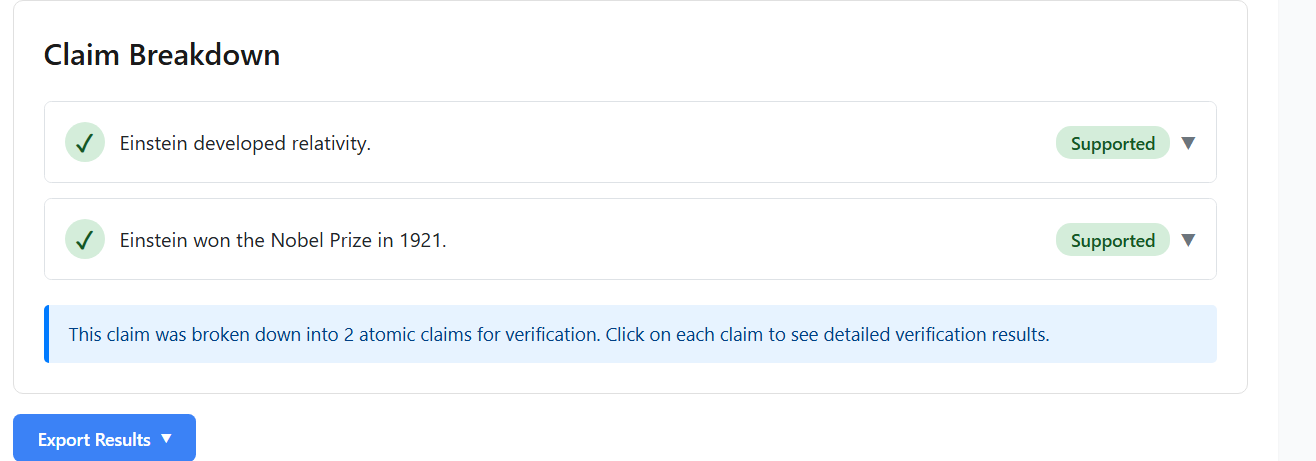

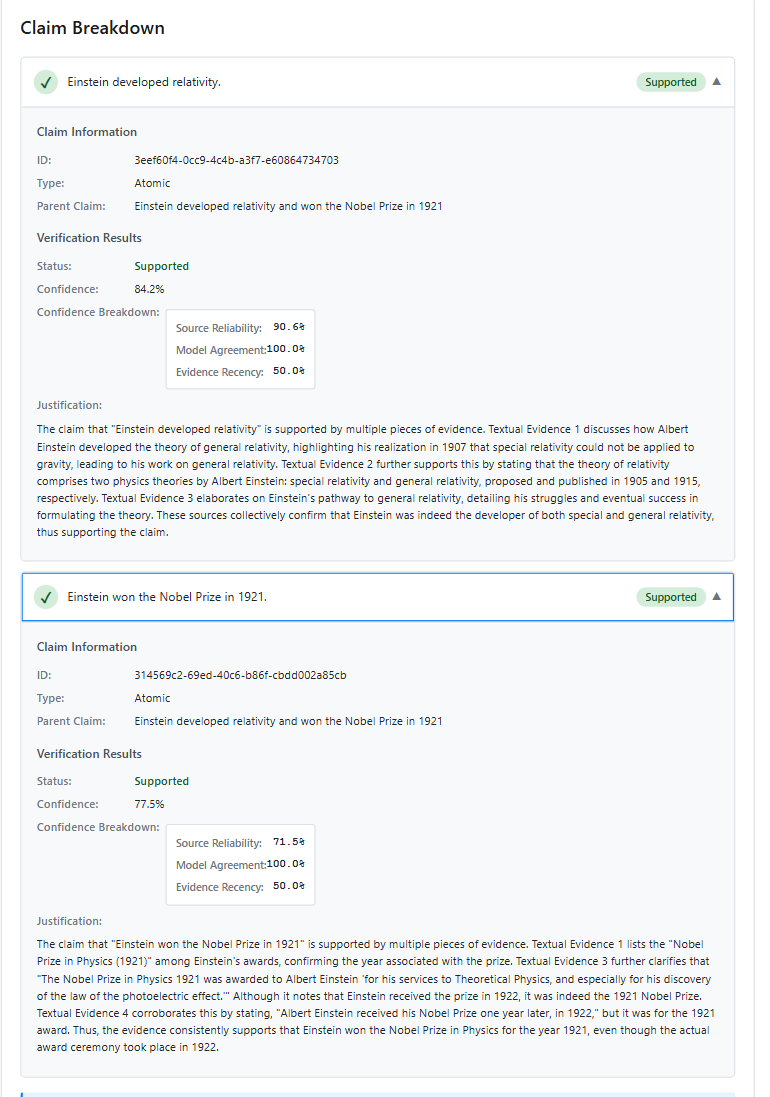

Atomic Claim Extraction: Complex claims often contain multiple verifiable statements. I use an LLM-based decomposition agent to extract atomic claims—minimal, self-contained factual statements that can be independently verified. For example, the claim “Einstein developed relativity and won the Nobel Prize in 1921” is decomposed into: (1) “Einstein developed the theory of relativity” and (2) “Einstein won the Nobel Prize in 1921.” Each atomic claim is then processed in dependently through the pipeline, with results aggregated at the end.

2. Evidence Retrieval

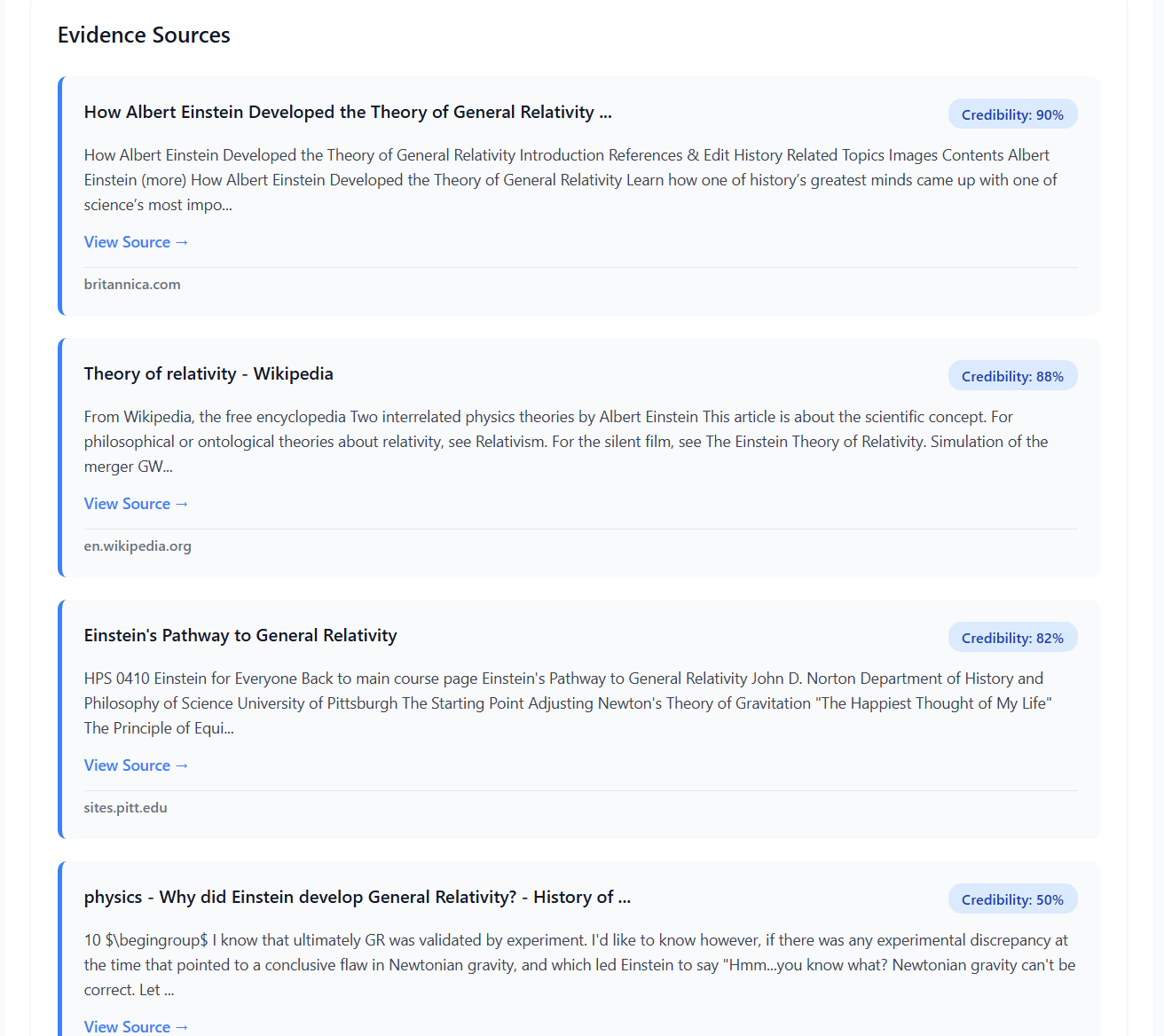

The Retriever Agent collects relevant evidence from live web sources using the Google Custom Search API. For each atomic claim, the agent first generates optimized search queries by extracting key entities and removing definitional language (e.g., “The Eiffel Tower is 330 meters tall” be comes “Eiffel Tower height meters”). The agent retrieves up to 10 relevant web pages per query, scrapes and summarizes content using Beautiful Soup and LLM-based summarization, applies temporal filtering to exclude sources published after the claim date, and filters out fact-checking sites (Snopes, PolitiFact) to prevent circular reasoning. For multimodal claims, the agent additionally performs reverse image search to find the original source.

3. Evidence Reranking

The Reranker Agent filters and prioritizes retrieved evidence using a weighted scoring function: $S_{final} = \alpha \cdot S_{rel} + \beta \cdot S_{cred} + \gamma \cdot S_{rec}$

where $S_rel$ is semantic relevance (computed via embedding similarity), $S_cred$ is domain credibility, and $S_rec$ is recency score. We use $α= 0.4$, $β =0.35$, $γ = 0.25$ based on empirical tuning

Domain Credibility Scoring: Sources are ranked by authority level: high credibility (0.9 - 1.0) for academic papers and government sites (.gov, .edu); medium (0.6–0.8) for verified news outlets (Reuters, AP, BBC); and low (0.3–0.5) for blogs, social media, and unknown domains.

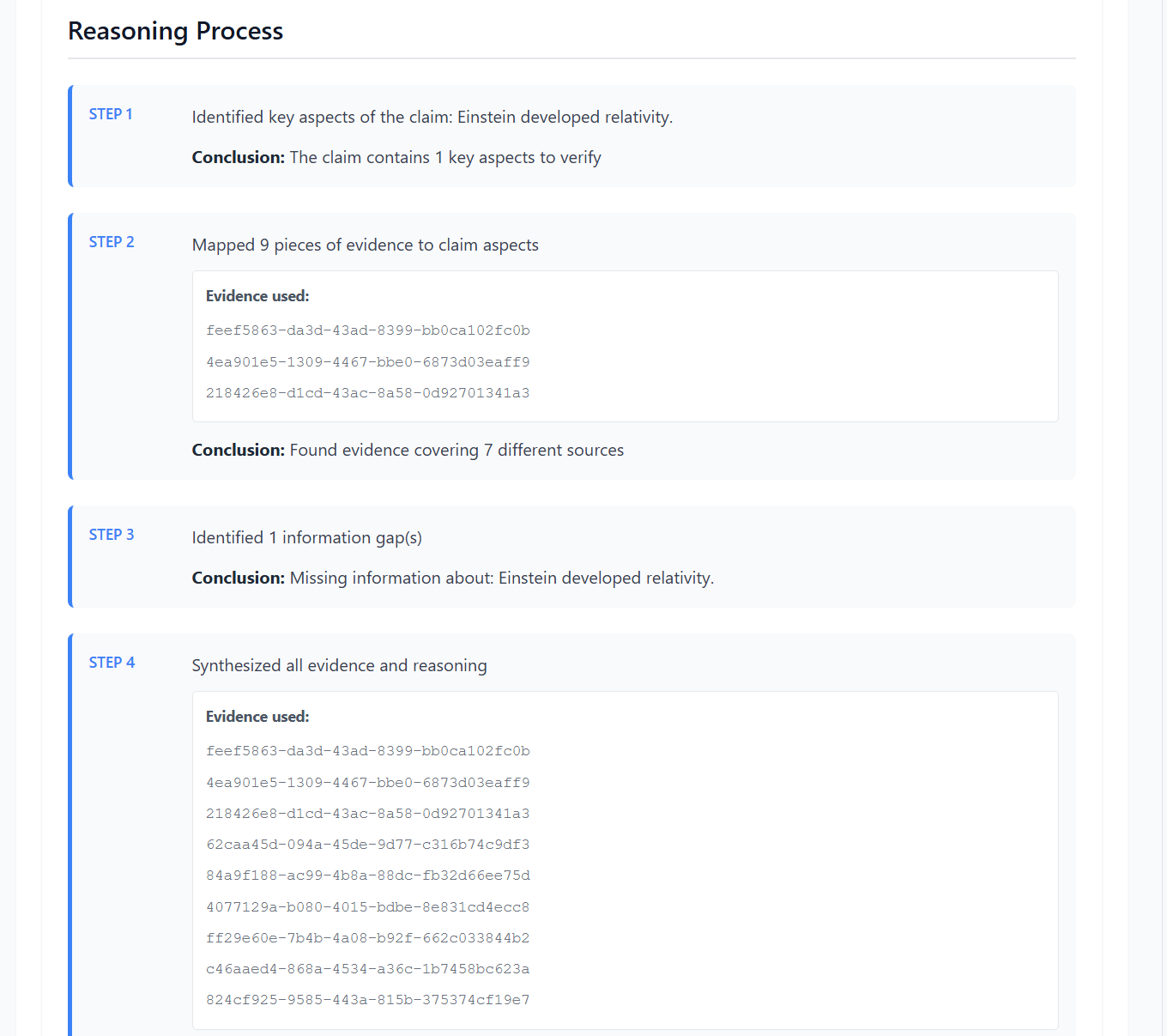

4. Evidence Aggregation

The Aggregator Agent consolidates evidence from multiple sources and applies chain-of-thought reasoning to identify agreements (corroborating evidence), conflicts (contradictory information), and gaps (missing information needed for verification). This structured evidence summary enables LLMs to reason over synthesized information rather than raw text.

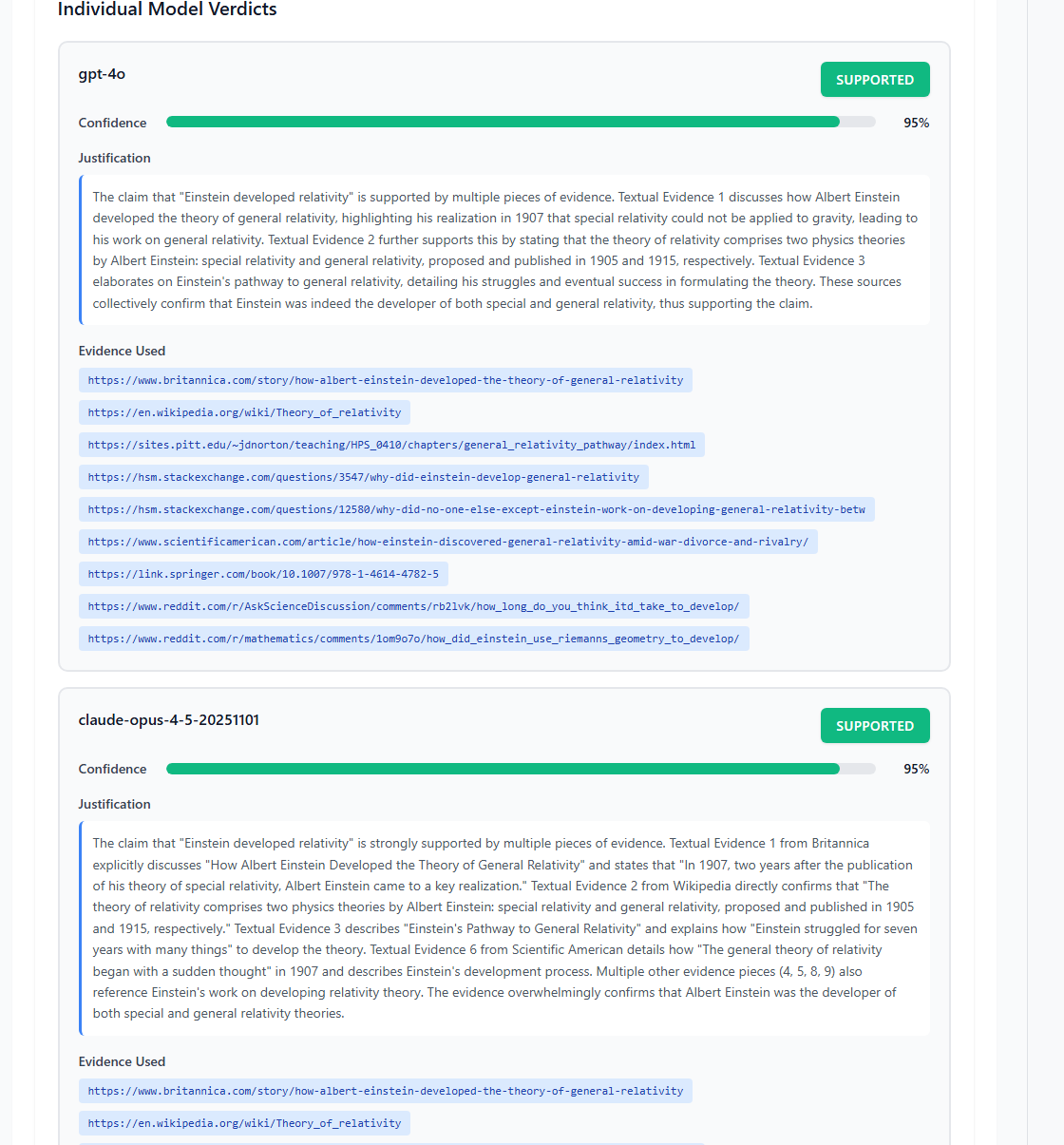

5. Multi-Model Verification

The Verifier Agent engages all user-selected LLMs in parallel. Each model receives identical context: the atomic claim, aggregated evidence, source metadata (URLs, domains, publication dates), and chain-of-thought reasoning from the aggregator. Each LLM independently produces a verdict v ∈ {Supported,Refuted,NEI} with a confidence score c ∈ [0,1] and a natural language justification.

6. Verdict Aggregation

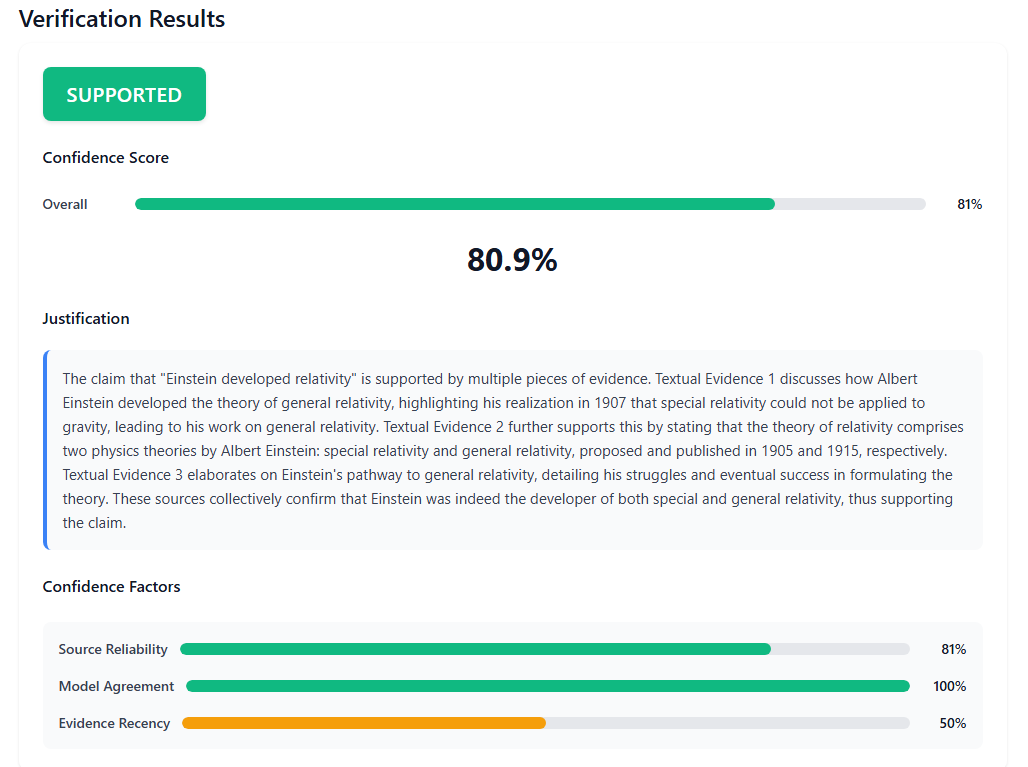

Individual verdicts are aggregated using a majority vote. $v_{final} = \arg\max_{v} \sum_{i: v_i = v} c_i$ When models disagree, the system reports agreement level and generates a consensus justification.

7. Confidence Scoring

The final confidence score combines three factors: $C_{overall} = w_1 \cdot C_{source} + w_2 \cdot C_{agree} + w_3 \cdot C_{rec}$ where $C_{source}$ is average source credibility, $C_{agree}$ is model agreement ratio, and $C_{rec}$ is evidence recency. I use $w_1=0.3$, $w_2=0.5$, $w_3=0.2$, weighting model agreement most heavily. The output includes structured justifications with source links, enabling users to verify the reasoning process.

Experiments and Results

I evaluated KEPLER on the FEVER dataset to assess verification accuracy across different LLM backends. Our experiments address three research questions: (1) How does model choice affect verification quality? (2) Which verdict categories are most challenging? (3) How do confidence scores correlate with accuracy?

Setup

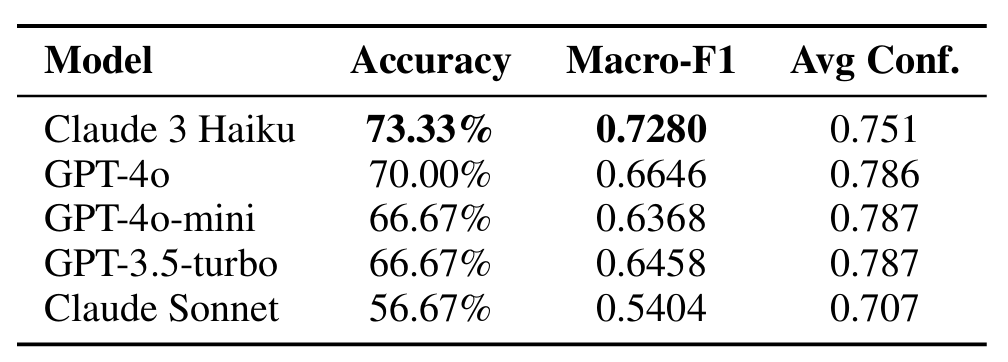

Dataset. I sampled 30 claims from FEVER’s development set, balanced across the three verdict categories (10 Supported, 10 Refuted, 10 NEI). This balanced sampling ensures fair evaluation across all classes. Models Evaluated. I tested five LLMs spanning different providers and model sizes: • OpenAI: GPT-4o, GPT-4o-mini, GPT-3.5 turbo • Anthropic: Claude 3 Haiku, Claude Sonnet Evidence Retrieval. All experiments use Google Custom Search API with rotating API keys to retrieve live web evidence. Each claim retrieves up to 10 sources, which are reranked and aggregated before verification. Metrics. We report Accuracy, Macro-F1 (averaging F1 across all three classes), and per-class F1 scores. Macro-F1 is our primary metric as it ac counts for class imbalance in predictions.

Findings?

Finding 1: Smaller models can outperform larger ones. Surprisingly, Claude 3 Haiku (the smallest Claude model) outperforms both GPT-4o and Claude Sonnet. This suggests that for fact verification, model size is less important than the model’s calibration and reasoning style. Finding 2: High confidence does not guarantee accuracy GPT-4o-minireports the highest average confidence (0.787) but achieves only 66.67% accuracy, while Claude 3 Haiku has lower confidence (0.751) but higher accuracy (73.33%).

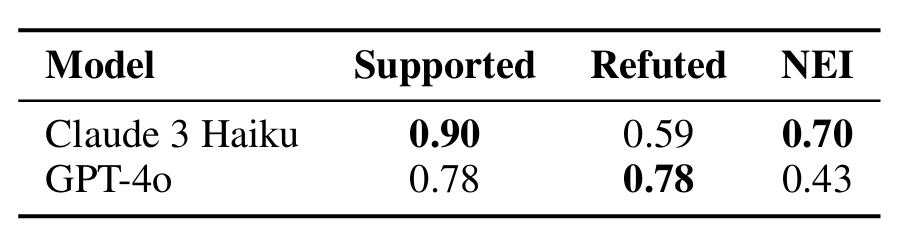

Finding 3: NEI is the hardest category. All models struggle with “Not Enough Information” claims. GPT-4o achieves only 0.43 F1 onNEI,fre quently misclassifying these as Supported or Refuted. Finding 4: Model strengths differ by category. Claude 3 Haiku achieves 0.90 F1 on Supported claims but only 0.59 on Refuted. GPT-4o shows balanced performance (0.78 on both) but fails on NEI.

Error Analysis

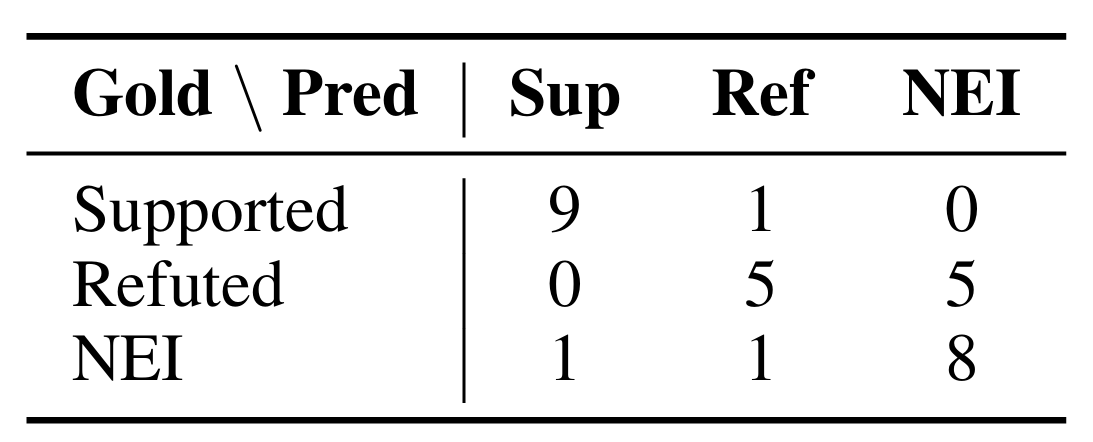

The confusion matrix reveals that Claude 3 Haiku’s errors primarily involve confusing Refuted claims with NEI. This conservative behavior

may be preferable in high-stakes scenarios where false refutations are costly.

The confusion matrix reveals that Claude 3 Haiku’s errors primarily involve confusing Refuted claims with NEI. This conservative behavior

may be preferable in high-stakes scenarios where false refutations are costly.

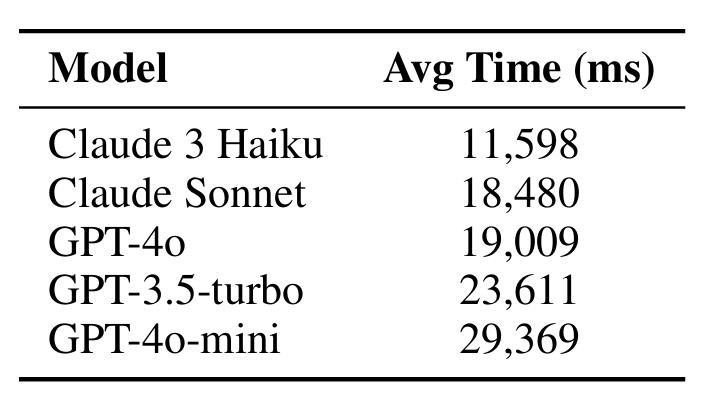

Processing Time

Notably, Claude 3 Haiku achieves both the highest accuracy and the fastest processing time, making it the most efficient choice for deployment. The majority of time is spent on evidence retrieval rather than LLM inference.

Discussion on Results

Why Smaller Models Outperform Larger Ones. The surprising finding that Claude 3 Haiku outperforms larger models like GPT-4o and Claude Sonnet warrants analysis. We hypothesize this occurs because: (1) Haiku exhibits more conservative behavior, preferring NEI over incorrect definitive verdicts; (2) larger models may be over confident, committing to Supported/Refuted even with ambiguous evidence; and (3) the task benefits more from calibration than raw capability. This suggests that for fact verification, model selection should prioritize calibration over size.

The NEI Challenge. All models struggle with “Not Enough Information” claims, with GPT-4o achieving only 0.43 F1 on this category. This reflects a fundamental tension in LLM design: models are trained to be helpful and provide answers, which conflicts with the epistemic humility required to say “I don’t know.” The confusion matrix shows models frequently misclassify NEI as Supported (false positives) or Refuted (false neg atives), suggesting they find patterns in evidence that humans would consider insufficient.

Confidence Calibration Issues. The results show that confidence scores are poorly calibrated across models. GPT-4o-mini reports the highest confidence (0.787) but achieves only 66.67% accuracy, while Claude 3 Haiku has lower confidence (0.751) but higher accuracy (73.33%). This miscalibration limits the utility of confidence scores for downstream decision-making and suggests that confidence-weighted aggregation may not always improve ensemble performance.

Evidence Retrieval as Bottleneck. Processing time analysis reveals that evidence retrieval dominates latency (11-29 seconds per claim), with LLMinference contributing minimally. This suggests optimization efforts should focus on retrieval efficiency rather than model inference speed.

Summarizing

KEPLER is a modular, LLM-based fact-checking system that addresses the challenges of fact-checking with a modular pipeline. It is designed to handle complex claims, dynamically collect evidence from the web, and provide structured justifications for reasoning. The system is currently deployed on a small scale and is open to contributions.

Link: https://kepler-two.vercel.app/